Shopping for a Diamond Is About to Change

The world’s most productive mine has closed, so your next piece of inexpensive jewelry probably will feature a lab-grown gem.

By Victoria Gomelsky via The New York Times

Nov. 17, 2020

Diamond mines are not forever — not even the world’s most productive.

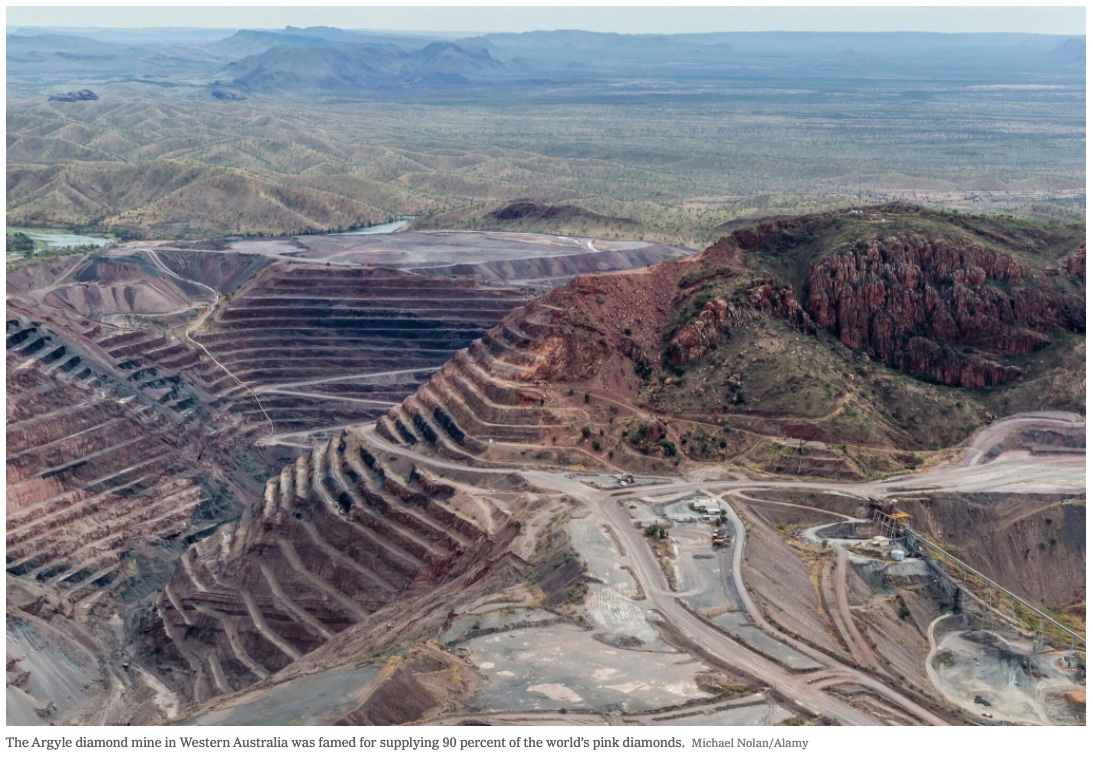

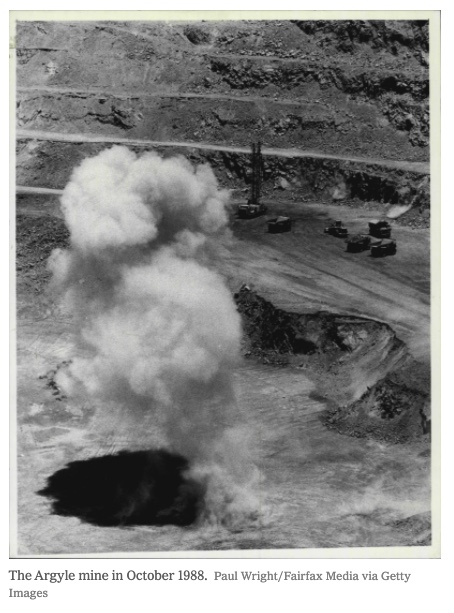

After mining more than 865 million carats of rough diamonds since opening in 1983, the Argyle Mine in the remote East Kimberley region of Western Australia brought the last truck of diamond-bearing ore to the surface on Nov. 3.

The owner, the Anglo-Australian mining giant Rio Tinto, had announced in 2018 that, by the end of this year, it would no longer be economical to keep digging.

Argyle was famed for supplying 90 percent of the world’s pink diamonds, among the rarest and most valuable gems on earth. But it was also noted, if less celebrated, for its vast reserve of inexpensive brownish diamonds, many of them in colors and qualities once shunned by fine jewelers. The low-end product was embraced by the Indian cutting industry in the late 1990s, when manufacturers based in Gujarat began using the gems to make jewelry that could retail for as little as $199.

Now, the mine’s long-anticipated closure is prompting an industrywide conversation about the future of natural, or mined, diamond supplies at both the high and low ends of the market, and how competition from the thriving lab-grown diamond sector will reshape consumer demand in years to come.

It’s not something a future bridal couple or jewelry fan might notice for a year or two, but when dealers sell what remains of their Argyle stocks, pink diamonds are expected to become costlier, while lower-end jewelry made with natural diamonds may become more scarce.

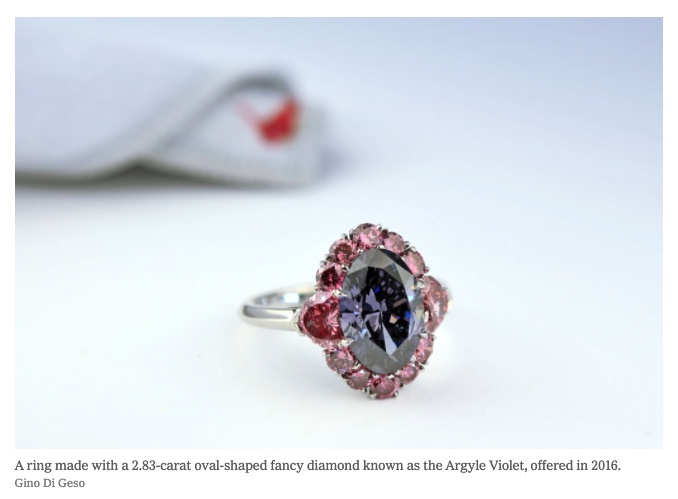

“Argyle’s closing is like the death of an artist,” said Larry J. West, owner of L.J. West Diamonds in New York, which deals in fancy colored diamonds. “After Picasso died, what was his best art worth?” (Mr. West should know. In 2016, he purchased a 2.83-carat oval-shaped violet diamond at Rio Tinto’s annual silent tender, a trade auction of its small but extremely valuable cache of rare pink, red, purple and violet diamonds each year. “It’s impossible to value because it is so rare,” he said.)

All of this, however, doesn’t mean the end of pink diamonds.

Alrosa, a mining company partially owned by the Russian government, occasionally discovers spectacular pink diamonds at its mines in Yakutia, in Russia’s Arctic region. (Take the 14.83-carat fancy vivid purple-pink diamond unearthed in 2017 at the company’s Ebelyakh deposit; named the Spirit of the Rose, it sold for $26.6 million at Sotheby’s Magnificent Jewels sale on Nov. 11 in Geneva.) But without Argyle’s consistent supply, high-end jewelers are bracing for prices to rise.

“Over the last six months, pinks have started to firm up in pricing,” said Tobias Kormind, managing director of 77 Diamonds, an online retailer based in Britain. “People are aware that the Argyle mine is closing. Interest rates are low, people are worried about inflation and deflation and they’re looking for alternative assets to put their money in for wealth preservation.”

A good quality one-carat intense pink diamond retails for approximately $250,000 and a vivid pink goes for more than twice that amount, about a 15 percent increase over last year’s prices, Mr. Kormind said.

For a polar opposite perspective, consider what industry watchers have to say about the end of Argyle’s brown diamond production.

“That’s the area most vulnerable to inroads from lab-grown diamonds,” said Russell Shor, a longtime industry analyst based in Carlsbad, Calif. “You’ll see a gradual substitution of lab-growns for Argyle goods in the under-$500 pieces. They’re made for that market, really.”

The extent to which lab-grown diamonds — which are optically, chemically and physically identical to mined diamonds — will supplant naturals has preoccupied the trade since at least 1955, when scientists at General Electric announced they had produced a synthetic diamond in a high-pressure, high-temperature growth chamber, simulating what happens inside the earth.

Until recently, however, retailers’ long-simmering mistrust prevented the lab-grown category from flourishing. That began to change about a decade ago, when jewelers realized the margins they stood to make on sales of lab-grown diamonds far exceeded those on naturals.

“A psychological barrier was broken among U.S. retailers,” said Edahn Golan, a diamond industry analyst based in Israel. “At first they viewed lab-grown diamonds as ‘synthetics’ and something a luxury retailer wouldn’t touch. That changed into ‘I’ll offer what my clients are asking for.’”

In the past five years, the lab-grown sector has welcomed countless newcomers, most notably, the South African diamond miner De Beers, which in 2018 channeled decades of expertise in creating diamonds for industrial purposes — through its Element Six division in Britain — into a fashion jewelry subsidiary called Lightbox.

At the end of October, Lightbox opened a $94 million manufacturing facility in a suburb of Portland, Ore., just as it announced a partnership with the leading online retailer Blue Nile. Lightbox sells one-carat white, pink or blue lab-grown diamonds for $800 (not including the cost of the setting), a striking difference from the cost of a one-carat natural diamond, which can range from $1,800 to $18,000. (Lightbox’s pricing, however, undercuts most lab-grown producers, whose gems sell for about 30 percent to 50 percent less than the equivalent natural diamonds.)

The essential difference between the two types of diamonds, said Stephen Lussier, De Beers’ executive vice president of consumer markets, hinges on their enduring value.

“It seems pretty clear that in contrast to naturals, the price of lab-growns will continue to fall,” he said. “Look at prices below a carat, where we’ve seen a 50 percent decline. That’s going to keep happening because of production capacity.”

Many lab-grown diamond sellers hope to transcend the fundamentals of supply and demand by positioning their product as the eco-friendly alternative to mined diamonds, even though the U.S. Federal Trade Commission has warned companies not to use unqualified claims to promote lab-grown diamonds as sustainable, given the large amounts of electricity required to grow diamonds.

Supporters of natural diamonds also cite the net positive effects some mining companies have on the communities where they operate, though critics maintain that environmental damage, forced labor and other issues continue to plague the industry.

Regardless, some have speculated that in 20 years, the debate will be moot.

“The bulk of the mines producing out of the ground are going to be way down in production or closed,” said Ben Janowski, founder of Janos Consultants in New York. “You have in the world a continuing desire for diamonds and it’s going to be filled by recycled diamonds, and the big hole is going to be covered by man-made diamonds.”

Executives at the cohort of major diamond mines left in the world today would likely dispute that assessment. (In descending order of the value of their rough diamond sales, they are: De Beers; Alrosa; Rio Tinto, whose Canadian mine, Diavik, is expected to close in 2025; Dominion Diamond Mines, based in Canada; and Petra Diamonds, owner of the historic Cullinan mine in South Africa.)

“Alrosa is sitting on at least one billion carats in the ground in Yakutia,” Mr. Golan, the Israeli analyst, said. “There are resources in Canada, Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo that haven’t been developed. So many places out there and this is just on land; we’re not talking about what’s available at sea.”

De Beers, which owns diamond mines in Botswana, South Africa, Namibia and Canada, has not disclosed its production forecasts beyond 2022, but Mr. Lussier said he was not worried about future supplies. “Technology is enabling us to access reserves we wouldn’t have been able to before,” he said.

“The key, of course, is demand,” he said. “It’s easy in the Covid world to get depressed. But if you look in the medium term, there are significant opportunities for demand to grow, particularly in China. There are even opportunities in mature markets like America, where self purchase is not fully tapped.”

“With the right marketing programs in place and brands working hand in hand,” Mr. Lussier added, “we’ll grow markets and where supply is relatively static, we’ll see increases in price. That’s a good thing for everyone in this industry. Then you’re willing to invest in new resources and exploration that keeps sustaining the supply of naturals out in the distance.”

The Natural Diamond Council, an industry organization that promotes mined diamond jewelry to both consumers and the trade, is investing millions of dollars to bring some of those marketing programs to life.

In September, the council, formerly known as the Diamond Producers Association, unveiled an advertising campaign with the tagline “For moments like no other.” Centered on a TV commercial and social media video featuring the Cuban actress Ana de Armas — who, coincidentally, stars as Marilyn Monroe in the forthcoming film “Blonde” — the campaign “is about the celebration of diamond jewelry in many relationships, whether it be with her friends, her mother or a romantic relationship,” said David Kellie, the council’s chief executive.

“How do you make diamonds relevant, cool and interesting for a younger audience?” he said. “It’s less about the formality and occasion-wearing, but about making them more appealing, informal and part of her everyday life.”

And yet it’s hard to forget that behind the emotional messaging about natural diamonds as an enduring gift of love, even if for oneself, is a practical question about what happens when they eventually run out.

For Eddie LeVian, chief executive of the Le Vian jewelry company, a family business with roots dating to 15th-century Persia, the Argyle mine’s closure is bittersweet in more ways than one.

Among the first fine jewelers to recognize the potential of Argyle’s brown diamonds, he began branding them in 2000 as “Chocolate Diamonds.”

Today, the company devotes a page of its website to “the end of the Argyle mine,” reminding customers that “these brown diamonds won’t be around for long.”

“There will always be demand for mined diamonds, even if there will not be enough of them to support that demand,” Mr. Le Vian said. “Some people may give up. But us hopeless romantics will keep searching.”

The brightest diamonds in the Argyle sky

During its 37-year run, the Argyle mine in Western Australia produced about 865 million carats of rough diamonds, the overwhelming majority of them small, brown and, ultimately, inexpensive.

Among connoisseurs, however, the mine, which closed Nov. 3, will be remembered for about 1,800 carats of cut fancy color diamonds — primarily pinks, but also reds, blues and violets. Rio Tinto, the mine’s owner, began selling these special gems in 1984 through an annual invitation-only silent auction called the Argyle Pink Diamonds Tender.

“Genuine scarcity, real beauty and a great Australian origin was the original vision for Argyle pink diamonds,” Mike Mitchell, general manager of sales and marketing for Argyle Diamonds from 1983 to 2003, and Rio Tinto Diamonds from 2003 to 2005, wrote in an email. “The tender itself was built around a highly coveted and carefully curated catalog, a very exclusive clientele and an almost mystical process that continues unchanged to this day.”

The cream of the pink diamond crop — about 1 percent of the mine’s annual production, or an average of 50 stones a year — would be selected for the tender held the following year. (If you gathered all the Argyle pink diamonds produced and sold at tenders, “you would barely be able to fill two Champagne flutes,” a spokeswoman for Rio Tinto Diamonds said.)

Continue reading the main story

Only about 100 collectors, luxury jewelers and diamond aficionados were invited to view the gems during their annual global tour, which typically began in July, and to bid on them by early October. (This year, the pandemic led to a two-month delay in the tender; 2020 bids are scheduled to close Dec. 2. There is expected to be a final tender in 2021, but a spokeswoman said planning has not begun.)

The 62 diamonds in the 2020 tender include six named stones, ranging from the 0.70-carat oval-shaped fancy dark violet-gray Argyle Infinité to the 2.24-carat round brilliant fancy vivid purplish-pink Argyle Eternity.

A 4.15-carat light pink radiant-cut diamond, offered in 2001, remains the largest ever presented at the tender. Other superlative gems include the 2.11-carat fancy red Argyle Everglow, offered in 2017; the 2.28-carat oval-shaped fancy purplish red Argyle Muse, auctioned in 2018; and a 2.83 carat oval-shaped fancy deep grayish bluish violet diamond known as the Argyle Violet, offered in 2016.

Larry J. West, owner of L.J. West Diamonds, a fancy colored diamond dealer in New York City, is the owner of the Argyle Violet, which he described as “another magnitude of rarity above the pinks.” He declined to reveal what he paid, or what its theoretical sale price would be.

“A decent quality two-carat Argyle tender stone probably starts at $1 million a carat, wholesale, and goes up,” Mr. West said. “But when you have something that’s going to cease to be produced, it’s really hard to speculate.”